When the tennis establishment welcomed professionals back into the fold after the sport went open 50 years ago there was as much interest in a 39-year-old Mexican American who was past his prime as there was in those men who would immediately become major contenders again for the sport’s biggest prizes.

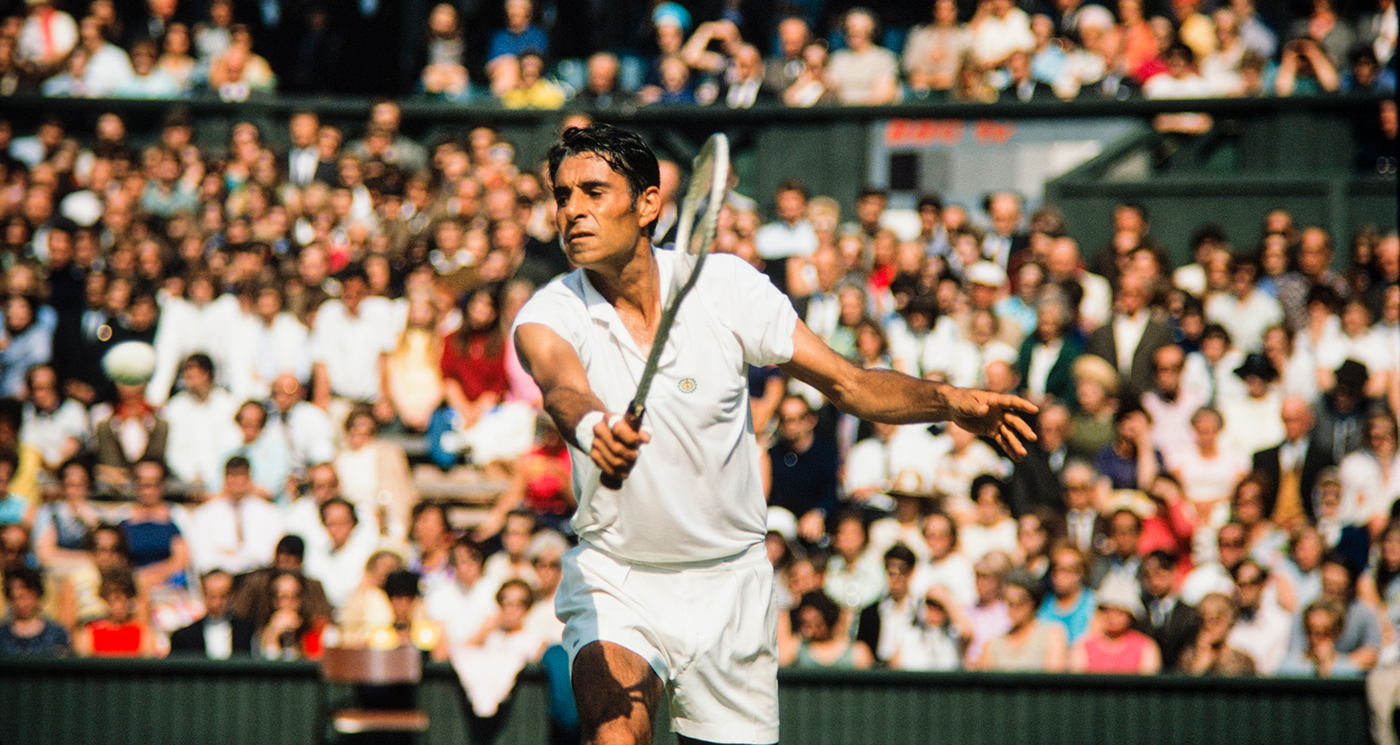

Richard “Pancho” Gonzales, who was born 90 years ago today, had not played in a Grand Slam tournament for 19 years, having turned professional at the age of just 21, but to some highly respected observers he was one of the greatest players in history. A superb athlete who stood at 6ft 3in tall and had remarkable stamina, Gonzales combined power with finesse and a cool tennis brain.

Jack Kramer, the 1947 Wimbledon champion, who went on to become one of the sport’s most celebrated promoters, considered Gonzales to be a better player even than Rod Laver, who won a pure calendar-year Grand Slam as an amateur in 1962 and repeated the feat in open tennis in 1969. “I’m positive that Gonzales could have beaten Laver regularly,” Kramer wrote in his autobiography.

Gonzales was brought up in Los Angeles by immigrants from Mexico. His parents could not afford to pay for tennis lessons, but from the moment Gonzales took up the game at the age of 12 his natural talent was evident.

Dark-skinned, Gonzales grew used to racial discrimination. Although he played at the Los Angeles Tennis Club he was not allowed to join because it did not admit non-white members.

At 19 Gonzales made his debut at the US Nationals (the tournament which became the US Open) and at 20, in only his second season competing at the highest level, he became the first non-white player to win the title.

Gonzales quickly developed a reputation as a rebel. He smoked, drank beer and played poker. There was inevitably huge interest in him when he made his debut at The Championships in 1949, where he was immediately installed as the No.2 seed.

However, the weight of expectation on Gonzales’ shoulders proved too much and he lost in four sets in the fourth round to Australia’s Geoff Brown, who had been runner-up in 1946. Gonzales did nevertheless win the gentlemen’s doubles title alongside Frank Parker.

At the US Nationals of 1949 Gonzales made a successful defence of his title by coming from behind to beat the American No.1, Ted Schroeder, 16-18, 2-6, 6-1, 6-2, 6-4. By that time Gonzales had set his sights on a professional career. Married with a young son and a wife who was expecting another baby, he had no other income. He knew that the only way he could continue in tennis was if he was paid to play.

Within days of his second victory at the US Nationals, Gonzales signed a contract worth a minimum of $60,000 to go on a professional tour with Kramer the following year. Kramer later said that Gonzales, who had only recently turned 21, was “still a baby” when he turned professional.

For the best part of the next two decades Gonzales got the better of most of his fellow professionals. He won a succession of tournaments, including the annual event at Wembley, where he was champion four times in the 1950s.

Although Gonzales had a reputation as a “difficult” character off the court, he always gave everything on it. Kramer wrote: “Gonzales took a lot of heat through the year for generally not co-operating. He sure wasn’t any prince. But if he were permitted to play, Gorgo would play.

“He’d scream at me until he was due on court, but then he’d go out there and play his guts out. He knew that a professional’s first obligation is to the public that buys the tickets and pays his bills.”

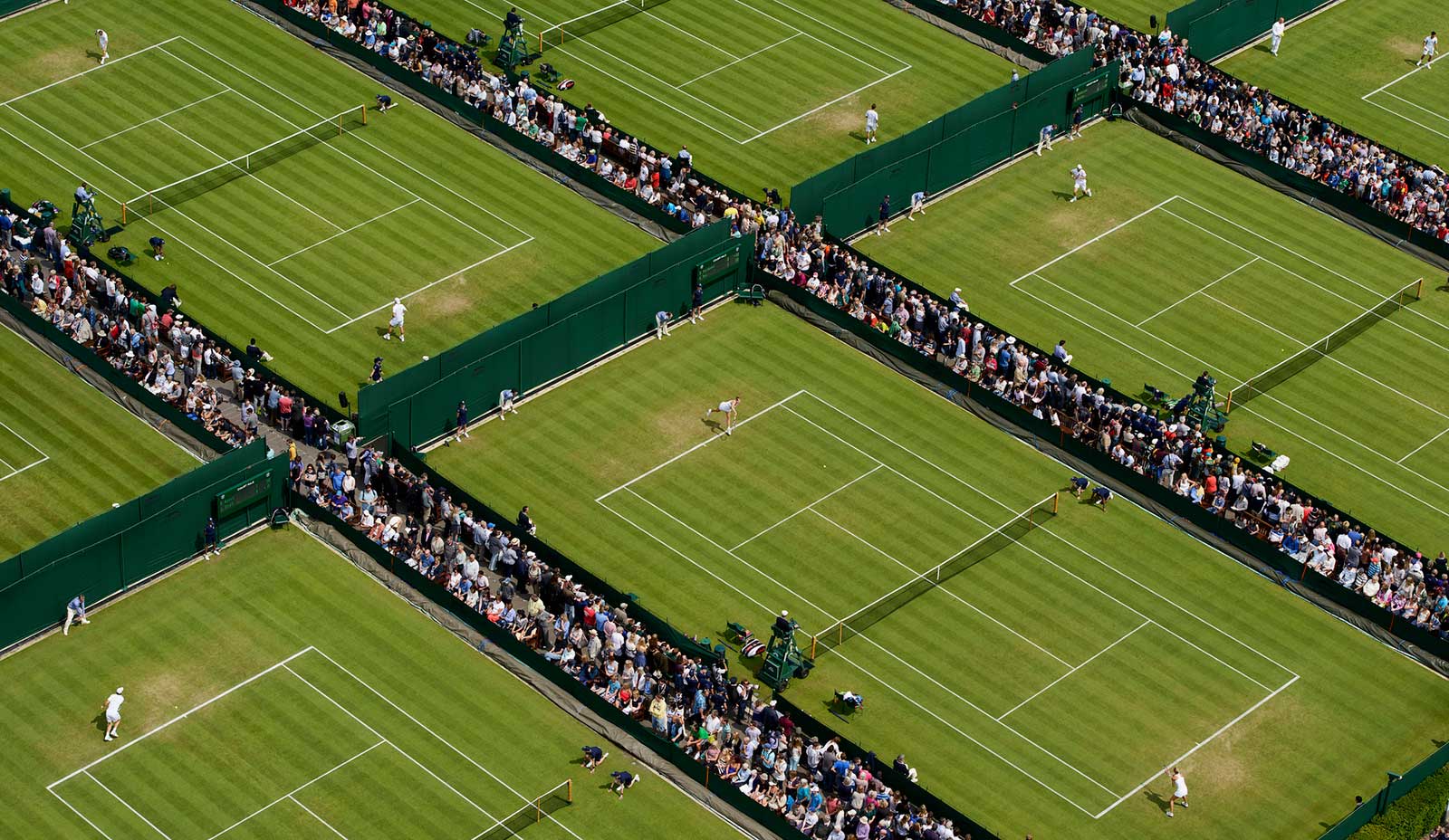

Gonzales was one of the eight players who played at Wimbledon in the summer of 1967 in a one-off professional competition. The event was such a success that the All England Club announced its intention to admit professionals and amateurs alike to The Championships the following summer.

In the spring of 1968 tennis made the historic decision to go open. Gonzales played in the very first open tournament, the British Hard Court Championships at Bournemouth in April, only to suffer a headline-making second-round defeat to an amateur, Britain’s Mark Cox.

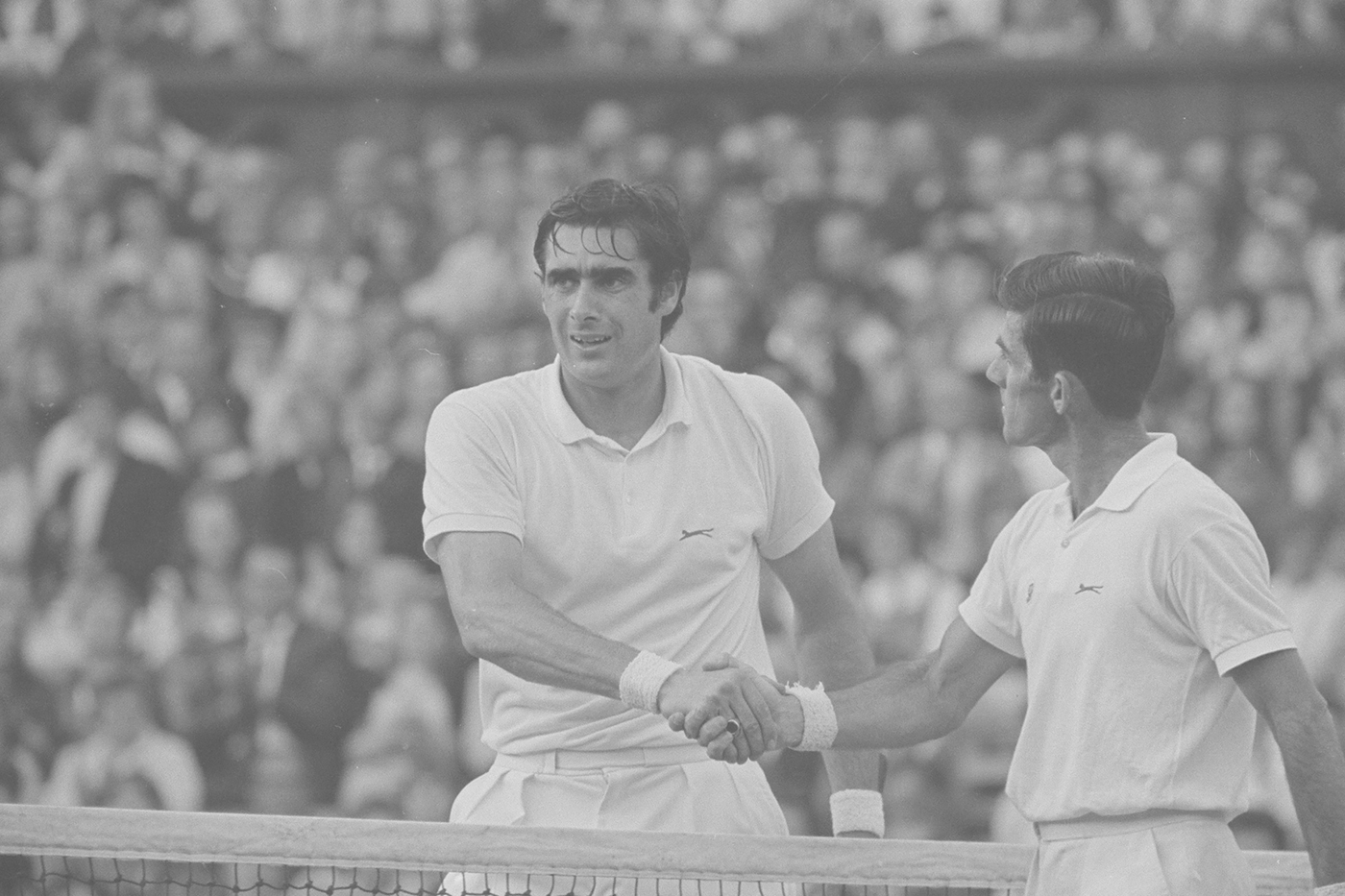

At the first open Wimbledon two months later there was huge interest in the returning professionals. Gonzales won his first two matches but was beaten by Russia’s Alex Metreveli in the third round.

Nevertheless, Gonzales’ finest moment at The Championships was still to come. In 1969, at the age of 41, he enjoyed one of the most famous comeback victories in Wimbledon history when he beat Charlie Pasarell 22-24, 1-6, 16-14, 6-3, 11-9 after five hours and 12 minutes. It remained the longest match in the history of The Championships until John Isner and Nicolas Mahut met in 2010.

I think that if you had to pick one player for a match in which you had everything at stake – even your life – it would be Pancho

Gonzales eventually lost in the fourth round to Arthur Ashe. He made only two more appearances at The Championships, going out in the second round in both 1971 and 1972. He retired from all tennis the following year and died in 1995 at the age of 67.

Before turning professional Gonzales had won two Grand Slam singles titles and two in doubles. How many more might he have won if he had not been exiled from Grand Slam competition for 19 years? Pasarell, a close friend, told Wimbledon.com: “We’ll never know, but I’m sure he would have won a bundle. He had amazing longevity in his career.

“Pancho had the heart of a lion. I’ve always said that there have certainly been other players who had better records than Pancho – and you can argue about whether Federer or Laver or whoever was the best player of all time – but I think that if you had to pick one player for a match in which you had everything at stake – even your life – it would be Pancho. He would find a way to win. I saw him do that time after time after time.

“He was a very tough, controversial guy. Some guys hated him because he was tough. But I think everyone respected him as a great champion.”